‘How I became an artist is more why I became an artist. First, it’s the form of expression that came the most naturally to me. Writing, making, drawing, and building things are all part of art making for me. But the why is more interesting. Very often as a young girl, when you grow up in a misogynist society, your voice isn’t heard. I realized one of the most effective ways to battle the injustices that upset me even when I was a child, was to make [art] and to write. I wouldn’t say it was to make change because it’s not possible in one’s lifetime. But it’s one of the most effective ways to be heard, to have a voice, and to be part of public discourse when you were very often pushed out of it.

How I became an artist: Shubigi Rao

Payal Uttam March 2, 2023

‘In the mid-80s, my parents gave up everything in the city and bought a small piece of land in the middle of a jungle at foothills of the Western Himalayas. It was in between two major national parks so there was a lot of wildlife. I went to boarding school, but I would stay there during the holidays. We built our own thatch bamboo and mud hut. We lived very simply, with no running water or electricity for the first few years. There were tigers, leopards, elephants, and occasional bears. Even as kids, my siblings and I were able to understand how to live and function [in nature]. The only time we ever faced threats was from human beings.

‘Living in the jungle was a brilliant experiment. At the time, nobody understood what my parents were doing. But now, looking back, it’s invaluable what they did. It’s very hard to communicate it – you have to live this life to know it – but non-human knowledge is actually spectacular. It’s far richer and more diverse than anyone could have imagined. And all these things informed me and built a sense of humility into my practice, which means that you realize that what you are doing is not so damn important in the grand scheme of things. We think human endeavor is the most important thing; each of us is in love with the things that we make and do. That’s a really dangerous phenomenon, because then we cause harm; we don’t care how exploitative we are or how we appropriate things, or how we use other creatures or resources in our quest for these things.

‘For example, when [the curator] Ute Meta Bauer and I were talking about the Venice pavilion, before the pandemic, we decided not to ship anything to the city. The only thing that traveled was a digital file which was emailed. We were very clear about the fact that it is possible to minimize harm [to the environment]. You can’t completely eliminate it, unfortunately – all this came from my upbringing.

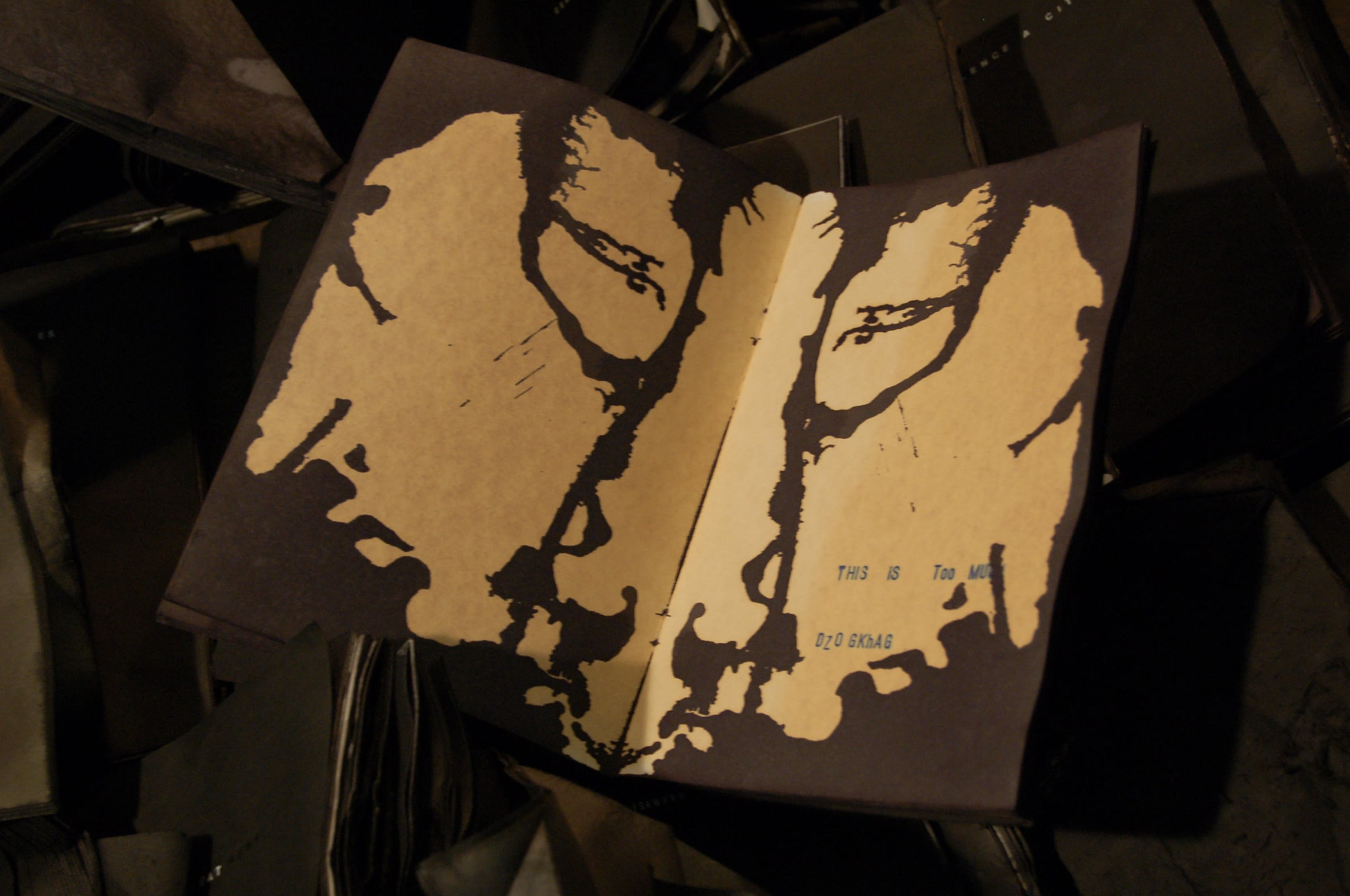

‘Interestingly enough, the pivotal moments for me have never been shows [like Venice]. But the work that I’m going to be showing in Encounters at Art Basel Hong Kong relates to a truly pivotal moment in my practice. During my MFA, I made a work called River of Ink with 100 hand-lettered books that I destroyed. It was a turning point. I knew I was going to continue this after I finished my 10-year project at the time, which was basically making all my work under a man’s name (S. Raoul) to talk about misogyny in the art world, academia, and science. It was a huge departure, because until then most of my work was satire. This was the first work that I did on cultural genocide. It was a coming together of all the things that were brewing in me – this anger that I always had at injustice. Not just censorship, silencing and erasure, but violence against people, the planet, and species. The work at Art Basel Hong Kong is a version of River of Ink but it’s a new work. It’s three times the size but I used a similar method. Because books are very hard to destroy, you have to soak each book page by page; so it’s quite laborious as it was 300 books. A lot of people think that the books are burned, but it’s just ink. It’s a symbolic action because ink is what we use to create, what we use to express ourselves and communicate, but that’s the very medium of destruction here.

‘The idea behind River of Ink is that it is a survivor’s account after the Battle of Baghdad in 1258 at the height of the Islamic Renaissance – a huge flowering of culture, mathematics, science, art, and literature. The libraries were mainly staffed by women who were at the forefront of knowledge making and dissemination. This library was destroyed when the city was captured by the Mongols in 1258. A survivor’s account says on the first day the rivers ran red with blood and on the second day black with ink because they dumped all the contents – priceless manuscripts from the library – into the river. So, the river of ink is this indelible image that I’ve always had. It symbolizes not only this one battle but this entire assault on creativity, free expression, diverse forms of thinking; the assault on minorities, on women, and assaults on basically anyone who contravenes dominant narratives.

‘Books and libraries are really a cover for talking about violence. What I’m really talking about is why our species is so fucked up. That’s what my work is about. I know that people don’t want to hear this stuff, so I use a cover story. I always use something else as the vehicle to talk about what I really want to talk about. I don’t do things directly. I think it’s important to slip an idea across in a gentle or subversive way, rather than be upfront about it.’

Shubigi Rao is represented by Rossi & Rossi (Hong Kong). Her work River of Ink II will be on view in the Encounters sector at Art Basel Hong Kong, which runs from March 23–25, 2023. For more information about the Encounters sector artists and galleries please click here.

Payal Uttam is an independent writer and editor who divides her time between Hong Kong and Singapore. She contributes to a range of publications including Artsy, The Art Newspaper, South China Morning Post, and The Wall Street Journal.

Caption for both full-bleed images: Installation view of Shubigi Rao, River of Ink (detail), 2008. Courtesy of the artist.